Pension customer journey and value framework

Understanding how people value pensions is critical to encouraging positive behavioural changes for retirement saving. It forms the basis of supporting optimal decision making and engagement throughout the pension customer journey, from accumulation through to drawdown.

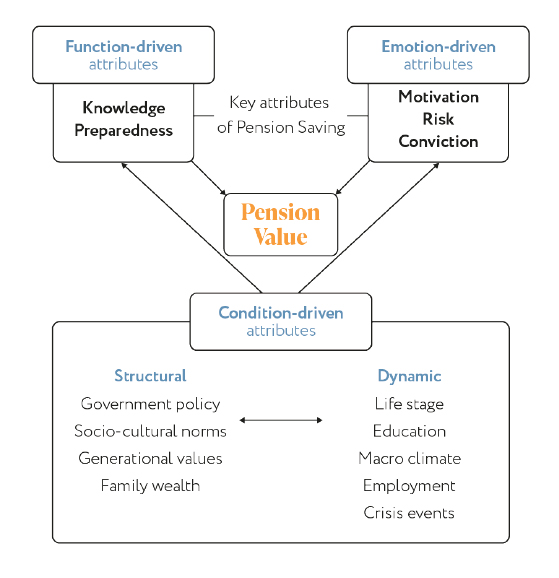

Our research shows that the path to a comfortable retirement is shaped by the perceived value of pension saving which is underpinned by five key factors:

• Knowledge - understanding pensions and how they work

• Preparedness – access to the financial skills and resources that enable saving

• Motivation – desire and enthusiasm to save for retirement

• Conviction – perceived importance of saving for retirement and level of trust relating to pensions

• Risk – willingness to accept a degree of risk with pension savings

These five attributes can be broadly classified as either ‘function-driven’ or ‘emotion-driven’, as shown in the pension value framework below (Fig 3).

However, they are also impacted by external factors such as life stage, education, economic shocks, government policy and many other factors. This means that there is also a set of condition-driven influences (structural and dynamic in nature), acting as a background stimulus component within the framework.

Figure 3: The UK Pension Landscape

Source: Retail Economics, Nutmeg

The pensions customer journey encompasses the decisions consumers make along the way, and the various touchpoints on their path – from initially considering a pension, to receiving ongoing support from a provider once retired. Key decisions include: when to start saving, how much to save, which savings vehicle to use, how and when to seek pensions advice and access savings. Some consumer decisions are ‘conscious’ (e.g. making an active choice after seeking information), while other decisions are more ‘unconscious’ (e.g. remaining in a default fund).

In reality, the customer journey is not linear. It is shaped by a continuous trade-off between short-term and long-term aspirations. Life events such as buying a house, getting married/ divorced, or having children, often lead to unpredictable income and spending.

Although the underlying incentive to save is to be able to enjoy retirement by drawing a pension which will enable a similar lifestyle to that enjoyed during one’s working life, life events can stifle regular saving. In addition, pension saving is illiquid with a pay-off that can feel far into the distant future for people.

Given these factors, people’s attitudes and behaviours can often result in having saved less for their retirement than originally anticipated. Misplaced faith in alternative sources of income during retirement (e.g. housing assets, inheritance or the level of state pension) can lead to unexpected consequences.

Influence of affluence

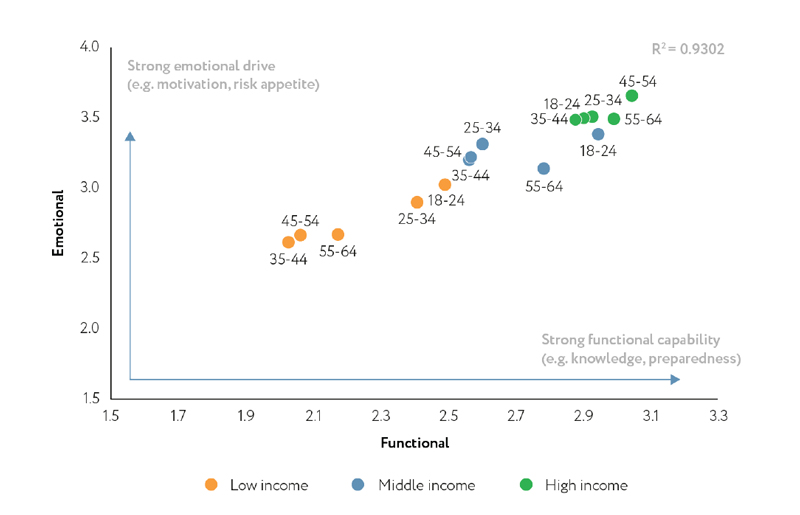

Affluence appears to be a significant influence across both the emotional and functional plains of the pensions value framework. Our research shows a strong correlation between income and a rise in the perceived value of pension saving (Fig 4). As household incomes increase, the emotional and functional drivers that support saving for retirement also rise, reflected in higher pension uptake levels too.

Figure 4: Correlation between income and perceived value of pension saving

Source: Retail Economics, Nutmeg

Those on higher incomes are more knowledgeable about pensions, feel prepared for retirement, have the economic means, and are more comfortable with taking investment risks. Whereas the least affluent feel less confident making financial decisions, are more hard-pressed financially, but also demonstrate lower motivation and engagement with pension saving.

These factors manifest in low income individuals being three times more likely to be without any pension savings than the most affluent, according to the research.

Lower engagement across the least affluent is also likely to reflect a higher proportion of individuals who work across multiple jobs, with workers only eligible for auto-enrolment if earning above £10,000 per annum in a single job with... [extract]

Download your FREE copy of this report by completing the form at top of page...

But even those that do meet the criteria, may see themselves as better off not saving for retirement, at least temporarily. Their current financial situation might be precarious, due to high debt levels or low income in which to cope with rising living costs. In fact, almost half (47%) of households earning below £11,000 per annum say they have ‘no money left over’ after paying for essentials, with almost one in five (18%) admitting borrowing money (e.g. bank loan, family, friends) to help cover everyday costs in the last six months due to the cost-ofliving crisis.

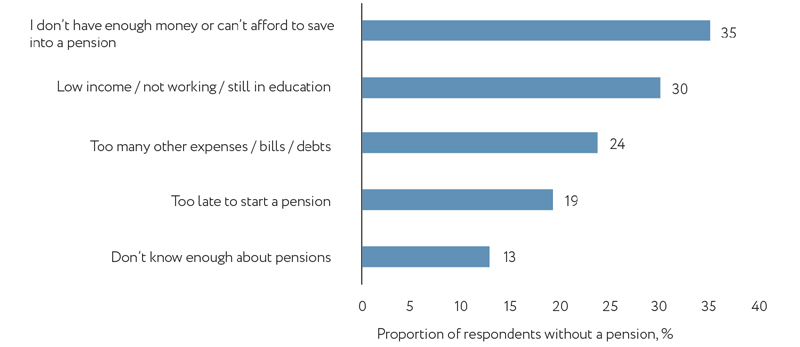

Among those without pension savings, the top three explanations were all related to financial concerns. The research found that:

• 35% (a staggering 5.3 million people in the UK) said that they do not have a pension because they “don’t have enough money to save into a pension”

• 30% said “I’m not working and my income is too low”

• And 24% said “I have too many bills or debts to pay”

Figure 5: Top five reasons people don't have a pension

Source: Retail Economics, Nutmeg

Opting out of a pension or reducing contributions represents an attractive option for struggling, low-income workers, at least temporarily, until they are in better financial

shape.

This takes on greater significance in the context of the cost-of-living crisis. With many low (and even middle-income) households struggling to afford essentials like food and energy, saving for retirement is likely to fall lower down in peoples’ priority lists.

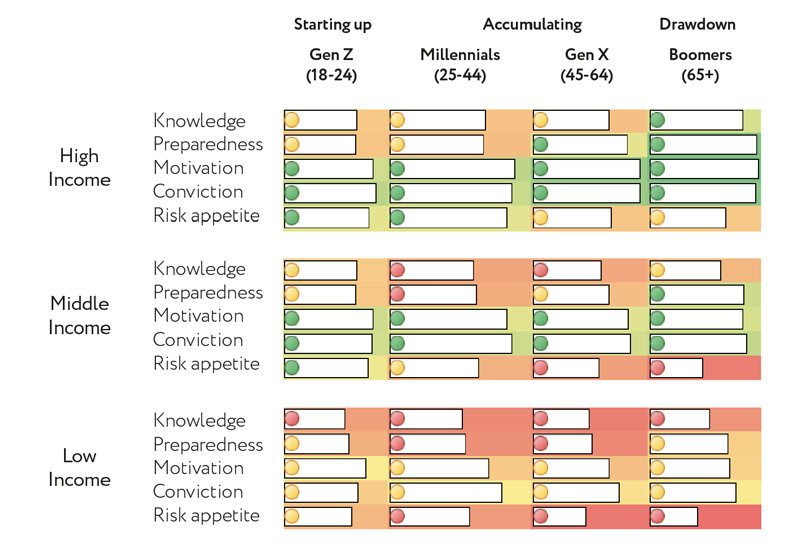

Figure 6: Pension value attributes vary by income and life stage

Source: Retail Economics, Nutmeg

Pension personas

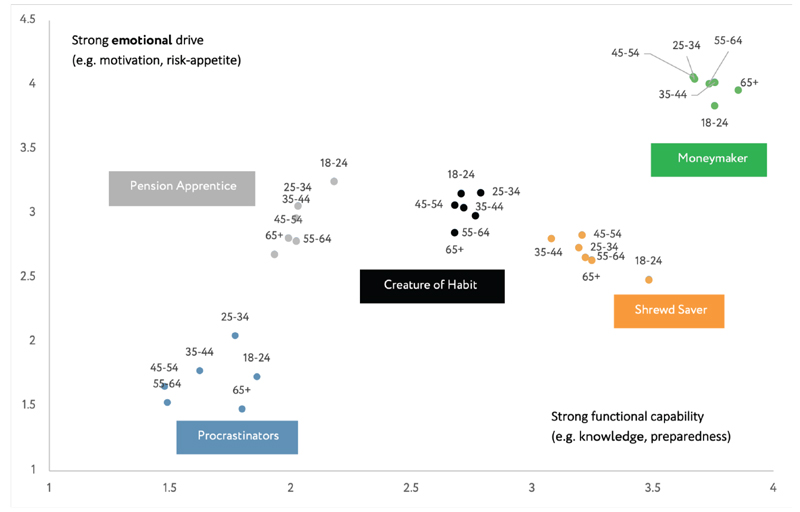

Broad demographic features such as age or income provide only limited insight about people’s approach to pensions and retirement planning. Ultimately, the pension customer journey is highly personalised and best understood through the lens of individual personas or mindsets.

Using cluster analysis (a statistical method to group datapoints based on common characteristics), five distinct pension personas emerge. These personas reflect shared attitudes and behaviours towards saving for retirement.

Consumers can also transition from one persona to another, depending on life stage, changes to their financial situation, and acquiring new skills/support.

Based on their level of functional and emotional pension value attributes, our research shows that UK consumers are aligned to one of the five pension personas below:

Figure 7: The five types of UK pension personas

Source: Retail Economics, Nutmeg

Moneymakers are highly motivated and knowledgeable with pensions and are on a strong path to achieving financial freedom in retirement. This cohort are significantly more comfortable taking risks with their investment decisions than other personas, deeming this to be necessary in their quest for maximum returns in the long-term. In fact, Moneymakers are four times more likely to say that they are ‘extremely comfortable’ taking risks with their pension (or financial investments) compared with the average.

The next type of personas is Procrastinators these people tend to....

Download your FREE copy of this report by completing the form at top of page...

We hope you found this article interesting. For more insights and industry analysis be sure to connect with us.

About this report

This report produced by Retail Economics in partnership with Nutmeg looks at the state of pensions in the UK. It offers guidance for current and future retirees on the level of savings and income required for retirement. The research can also be used to support financial providers in helping them develop effective strategies, and to better engage clients. The research also presents a calculation for the shortfall between current pension pot values and the income needed for a comfortable retirement.

View All THOUGHT LEADERSHIP REPORTS